Walking toward the front entrance of my new middle school for the first time, I was shocked with how different it looked from schools in Los Angeles.

In South Korea, the schools are typically one long, narrow building that climbs several stories into the air. It makes sense, though — when it snows, rains, or thunders, it’s good to have everyone indoors. In Los Angeles (and other areas of Southern California), schools are spread out with many detached classrooms, bungalows, and small buildings with a lot of open air.

Off to the south, the playground was a long, wide dirt field that didn’t have one single blade of grass. Hell, the basketball court and soccer pitch was on dirt!

Since it was the first day of class, my school hosted a parent-student assembly in the large auditorium to welcome the kids. I stood in the back of room during the principal’s speech, but I had no idea what was going on or what to do; I couldn’t understand a lick of Korean and none of the parents could tell the difference.

At that moment, I realized I was both the first-ever-native-English teacher and the first-ever-native-English-teacher-who-didn’t-look-like-a native-English teacher. Oh joy. After the ceremony, I walked around the room and a few parents gave me a respectful bow; perhaps they thought I was the new science teacher?

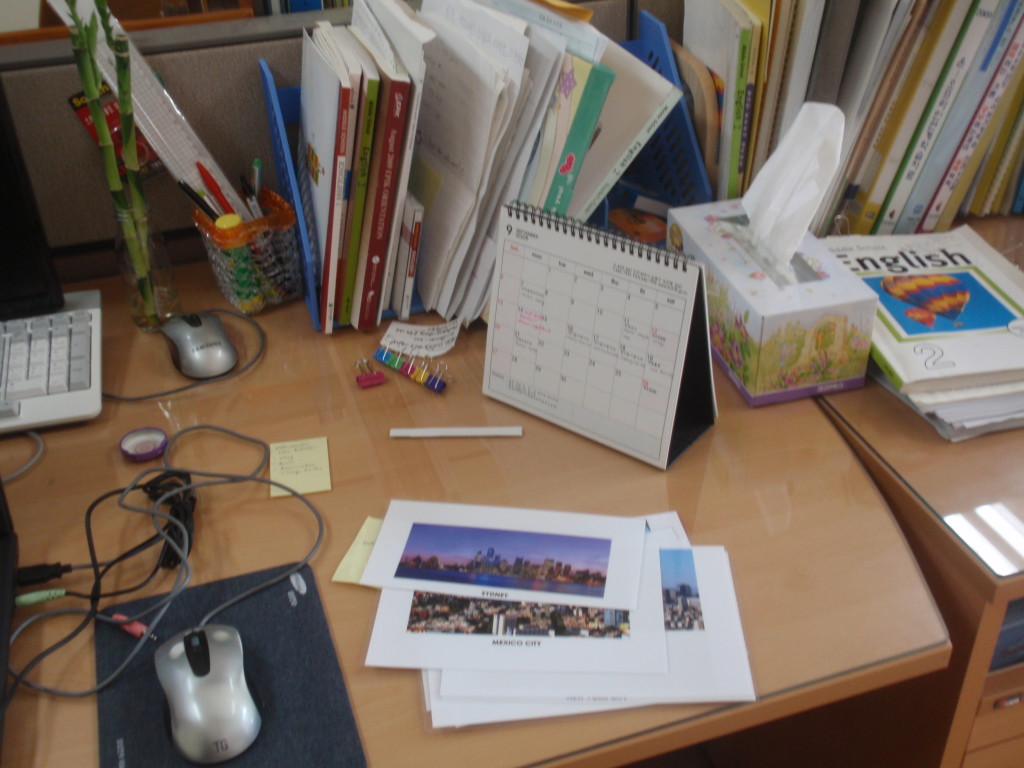

Soon, my coteacher led me to my new office for the year: a small room on the second floor, toward the end of the building, with a few desks pushed together to make one huge table at the center; each teacher had their own chunk of table, separated by short barriers. My seat was just left of my coteacher. I sat down at my desk and noticed two gifts from my school: a towel and a box of rice cakes.

“Would you like to tour the classrooms?” my coteacher asked.

“Sure, why not?” I said.

I strolled through the empty hallways and went from class to class, sitting in the back and watching how schools in South Korea operated. I found my first classroom, opened the sliding, wooden door, and sat in an empty chair in the back of the room as every single student stared at me.

The room had about 45 kids cramped inside with just one teacher at the front with barely any space for the teacher to pace the aisles. Other than that, however, it was very similar to American schools: some kids were paying attention, some were messing around, and a few were sleeping. (But, hey, if I was a middle school student, I would be sleeping too.)

As the first-ever native English teacher at Nonhyeon Middle School, I was responsible for teaching the sixth and seven grades, with each grade containing twelve classes and each class containing about 45 kids. Holy shit, I thought, that’s over one thousand students! They didn’t waste anytime throwing me into the fire. (I never asked about the eighth graders; perhaps my school thought it was too late for them?)

During my first meeting with a few of the Korean English teachers, they recommended that I create two lesson plans per week — one for all the sixth grade classes and one for all the seventh grade classes — since I saw every class only once a week. Also, every week, I would alternate between a lesson from the textbook that coincided with what the Korean-English teachers taught and a lesson of my own. “Make it fun,” they suggested. Gotcha. Fun? I can do that. And I have the perfect idea.

I knew that on the first week, all the students were probably as excited to learn about me as I was to learn about them so, for that lesson, I only wanted them to have a lot fun, ask a lot of questions, and get more comfortable with English speakers. Before the big day, I walked into to my classroom, a brand-new, bright room with computers, a fancy projector, a surround-sound system, and more floor space than any other classroom in our school, and prepared for my first class.

The kids got to sit together in large tables of four so that everyone could work together in teams and interact, which was unlike every other class. I spent hours arranging all types of arts and crafts materials into plastic boxes, enough for each table, created animated Powerpoint slides, and organized my lesson. I hope they like it.

The day of my first class arrived. I walked to school, dumped my backpack off into my office, walked to my classroom, and turned on my main computer. After I readied my slides, I played some music on the speakers while showing the YouTube music videos on the projector screen. I didn’t want my class to be a stuffy, boring place — I wanted it to be fun, kinda like a party… just with English.

As the sleepy children filed into the room that morning, only a few seemed to notice the music, videos, or the bright classroom. By the time the bell rang, the students quieted down, my Korean coteacher gave me a smile and a nod, and we were ready to begin. Here we go!

“Good morning!” I yelled with all the chirpiness I could muster. “How are you?!”

Silence.

Uh, is this thing on?

I tried again. “Good morning!” I yelled more enthusiastically while motioning for everyone to reply. This time, a handful of students mumbled a response. Not a good start. I smiled and slowly walked around the classroom to greet random students. “How are you today?” I asked one boy.

He instantly sat up ramrod-straight, widened his eyes, and darted his head towards the Korean-English teacher and back at me. “Um,” he stuttered, “pine.” (That was his pronunciation of “fine” because the “f” sound doesn’t exist in the Korean language.) Oooookay… I walked over to the next student — again, no response. What the hell am I doing wrong? I walked over to yet another student and, this time, she replied by stressing every syllable:

“IIIIIIIIIII’M PINE. TAANK YOOOUU… ummm… AND YOOOUU?”

Uh, let’s move on, shall we?

I strolled back to the front of the class and showed a quick slideshow with a bunch of pictures of me, my home, my friends, my hobbies, and why I came to South Korea. Originally, I wanted to show them my life back in America and build some rapport with all my new students; during the class, they seemed interested enough. Then, I opened the class to questions. When I was a kid, I remembered that whenever the teacher asked for questions, we’d all try to come up with as many as possible so we could delay the lesson. Perhaps this would give them the same opportunity to show how clever they were?

On class #1, the kids asked me if I could speak Korean. Well, no, I can’t. Then they asked me if I was Korean. Well, no, I’m not. Then they told the Korean teacher that I, indeed, looked Korean. Well thank you, but I assure you, I am not.

Did anyone have any questions unrelated to me being Korean or speaking Korean?

Nope.

Uh, let’s move on to the classroom rules, shall we?

I only had two: have fun and be respectful to others. The students stared at me like I just meowed. What the hell did I do wrong now? I repeated myself while using easy words to describe what I meant with the rules. Still nothing. “Uhh…” I said to my coteacher, “maybe you should translate this for them.” Honestly, I didn’t think the English I used was too complicated; I said it slow and clear and purposely used words that they would’ve already knew from prior years and lessons.

Uh, let’s move on to the lesson, shall we?

I gave each table a box full of crayons, colored pencils, and special pens and I told everyone that were going to spend Week One making name tags and sharing what made everyone unique. I thought it would be a fun way to slowly get them accustomed to English while still preserving their Korean heritage — all they had to do was take a piece of paper, fold it in half length-wise, and write their name in English as creatively as they wanted to while drawing and writing all their favorite foods, hobbies, places, and people in English.

Most of them knew how to spell their Korean name in English, but if they didn’t, I told them to ask the co-teacher to translate. (If they wanted an English name, I said, they could ask me, but it wasn’t required.) Then, I walked around the class just to chat with the kids, ask a few basic questions, translate a few things, and make sure everyone was following along.

Well, I learned a few harsh lessons that week. First, students in South Korea are largely unaccustomed to creative tasks and ambiguous goals. Many of them didn’t even know where to begin. I walked to their seat and knelt beside their chair:

“What’s your name?”

They would tell me their name.

“Okay. So go ahead and write that here,” I said while pointing to the center of their paper. Do you know how to spell your name?”

They nodded.

“Good! Now, uhh, what is your favorite food?”

“Hmm… pizza!”

“Great! Me too! Okay, draw a pizza on your nametag or write it on your paper. Here,” I said, grabbing some colored pencils from their box, “use some cool colors.”

By the end of class, however there were still many kids with blank pieces of paper in front of them regardless of how often I — or the Korean coteacher — helped them.

Second, a lot of students did not give a rat’s ass, even though all I asked them to do was write their name on a piece of paper and color some stuff. Some of them just wanted to talk with their friends. Another kid thought it would be funny to write, “FUCK” and “SHIT” on his nametag and draw swastikas with pencil. Gee, were his previous English teachers skinheads or something?

“Here, let me see this,” I said while picking up his nametag, crumbling it in my hands, and dropping it in a trashcan.

“Yeah, here’s another sheet of paper,” I said. “Do one without the symbols.”

Third, even though their textbook was at a moderately conversational level, these students couldn’t speak English worth a damn. Didn’t they already have five years of English classes by the time they reached middle school? Hell, only twenty minutes ago, I found out these boys and girls could barely comprehend English greetings. (I mean, I sucked in my high school French classes, but at least I knew “ça va” and “ça va bien.”)

It turned out that the extent of their English abilities covered just reading and writing — nothing else. After shadowing some English classes taught by the Korean teachers, I noticed that almost all of their lesson was spoken in Korean, while they sporadically shot English words or phrases like gunfire. Even among the teachers themselves, there was a huge range in English levels from pretty good to me not even knowing they were English teachers until months later.

Fourth — and this one is really indicative of my middle school — they really liked giving each other the finger. Wow. Did they even know what it meant? These kids were throwing up the middle finger in the hall, in the classroom, and in the schoolyard like they caught the Holy Ghost. Geez, I didn’t even see that many middle fingers in American schools. Those that weren’t busying their hands with vulgar gestures wrote notes in class or, if they were girls, combed their hair or checked themselves with pocket mirrors incessantly.

Good god, they’re twelve and they’re already worried about how they look?

The entire ordeal was fucking exhausting. I taught three classes before lunch, and I escaped with a few other teachers to the cafeteria for my first ever lunch break.

On the other side of wooden sliding doors, the cafeteria was a medium-sized room with the food station at one end. The line started by the door and, after grabbing a metal tray with round dimples to hold the food, you began with the kimchi and rice section, which was essentially a mandatory component of any meal in South Korea. They didn’t fuck around, however, with their kimchi: some days the shit was so spicy, even the teachers complained.

Then you’d shimmy to your left to scoop up their meat dish(es) and their veggie dish(es) and you’d finish by grabbing a plastic bowl for their special item, typically a stew, soup, or fried rice concoction. Yet, for school cafeteria food, it tasted pretty decent — sometimes, they’d have something sweet for dessert and sometimes they had diverse selections like pasta, dumplings, and fried fish. Compared to what I ate in my middle school, Nonhyeon Middle School won in terms of taste and health.

When I was twelve, my lunches would alternate between a baked potato, a chalupa, a slice of pizza, or an entire bag of Hot Cheetos. How did I not get scurvy?

During that first school lunch, I sat with my main coteacher and a few other teachers who kindly smiled at me. It was quiet, though; a little too quiet. Someone muttered something to my coteacher who relayed the message to me: “Everyone’s a little uncomfortable sitting with you.” Oh… why? “They don’t speak English.” No worries, I told her. I had her translate a message that I was very excited to be in South Korea and to work with them and they all seemed pretty pleased. One was the PE teacher, a well-built woman with short wavy hair, who was open, loud, and not encumbered by a silly little thing like shyness.

“Hiiii!” she said loudly. “Uhh… nice toooo meet youuu!”

“Nice to meet you too!” I said. “How are you?”

“Uhh… IIIII’m pine. Tank you. And yoooouuu?”

Where have I heard that before?

Twenty seconds later, I made an ass of myself (again). With all the hot, spicy food killing my sinuses, I grabbed a paper napkin and blew my nose.

HAHAHAHA!! Everyone roared in laughter and I froze. What the fuck did I do?

I worriedly asked my coteacher. “The way you blew your nose,” she said between fits of hysterical laughter, “made everyone laugh.” Lesson learned. Apparently, in South Korea, blowing your nose at the lunch table is NOT okay; from that moment on, I always ducked into a corner of the cafeteria or walked outside to blow my nose.

For the children, however, they had a different lunchtime ritual: when the bell rang signaling the mid-day break, all the boys sprinted back to their homerooms, grabbed baseball gloves and balls, sprinted outside, and converted their dirt soccer field into a pseudo-bullpen session. Within minutes, there was an entire battery of kids throwing fastballs and playing catch, while others played soccer and a few others played basketball.

A lot of girls played outside, too, with their own little games or hung out with their friends inside the empty classrooms. Unfortunately, all that disorder was louder than the Vietnam War: screaming, yelling, talking, and singing echoed through the halls, through the open windows, and even through my headphones. On those days I just wanted to rejuvenating solitude, I heard yelling everywhere. Kids sprinted and yelled through the hallways and others had the balls to play baseball in the halls. The teachers couldn’t give a fuck.

Thus, over the next three weeks, I desperately tried to solve the discipline problem. And it stemmed from something they never ever taught me in college, high school, middle school, or elementary school. Quite simply, the teacher sees everything. Did you think you were clever cheating, talking, or passing notes in your class? I would bet 100,000 Korean Won that your teacher saw you red-handed; she just didn’t want to say anything because she knew she had to pick her battles. Thus, every teacher had a different way to command the classroom because, well, every teacher was so different.

In South Korea, some teachers still hit children, which was allowed in the classroom. I remember one time I sat in my office and saw a kid get slapped hard on the back of his head several times while his parents sat five feet away. (Perhaps they were going to do the same when they got home?) That first week, I decided to simply send the troublemakers to the back of the class until I realized I often had about 25% of the fucking class standing in the back.

God, it was ridiculous: some days it seemed I ran out of space. And even at the back, they still had the nerve to talk to each other! Fuck this. It’s time to change things up. I saw on an online forum that other English teachers used yellow cards and red cards. Of course! It was the international symbol of warnings and punishment! The second they saw me hold a yellow card with a serious face, all the kids would know to get quiet because the red card was just moments away, right? Right?

Wrong.

Then, I tried turning off the lights when it got too loud, which worked only one time and then immediately became useless. Then, I made them do pushups, but I think they just enjoyed the exercise. Finally, I tried sending the worst offenders to the principal’s office, just like how you get sent to the principal’s or dean’s office if you get in trouble in middle school. God, that was miserable. First, no teacher in South Korea did that. Thus, when I sent the problem child to the principal’s office, the principal was utterly confused. Second, the teachers didn’t know how to enforce that policy because, again, nobody did that.

By then, I gave up. To me, it was better to have the troublemakers in my class, sitting in the back; at least that way, if they didn’t want to learn voluntarily, they could learn by osmosis. I remember one instance during my lesson when I caught a boy painting his fingernails with whiteout. “What are you doing?!” I asked him. “Teacher!” another kid piped up and yelled, “Gay!” while gesturing at White-Out Boy. I couldn’t help but laugh and saw that the coteacher who was giggling, too.

What could I say? Reprimand him for the insult? Hey, the kid had a point.

Finally, if you’ve never been to Asia before, I’ll give you a heads up: they use a different kind of toilet, often called a “squatty-potty.” It’s a tiny porcelain trough that sits on the ground. To take a shit, you need to stand directly over it, squat down as low as you can with your heels on the ground, and dump right into the bowl. If that wasn’t bad enough, they forbade you to throw your used toilet paper into the bowl and flush it away.

No, instead, you had to throw that nasty, smelly, shitty paper into a fucking trashcan next to the bowl. My school made the students use the gloried hole-in-the-ground while teachers had the magnanimous luxury of a Western toilet with an adjacent shit-bucket. One thing I soon noticed was that, when we all ate at the cafeteria, no one sat next to the old ladies who emptied out the doo-doo buckets. Gee, I wonder why.

There was one saving grace, though: when the final bell rings, Korean students run back to their homerooms; grab mops, brooms, towels, and hand cloths; and go to their assigned classrooms to clean. Clean! I couldn’t believe it! What kind of firestorm would ensure if they made American middle school students do that? (Lawsuits up the ass, maybe.)

They mopped our offices and classrooms and even dusted our tables: two boys or two girls would walk in to our office after school ended, give the teachers a respectfully deep bow, and become our personal maids for three or four minutes. One time, a girl pointed to an empty juice bottle on my desk and asked if she could throw it away for me.

I could get used to this, I thought.

What an incredible story!! Another world.

Ray, thanks my brotha! Hope things are well with you. 🙂

As a Korean-Chinese American (born in Korea, raised in in Hong Kong, now live in the US), your perspective is really interesting. I came across your blog because I was searching for some tinder stats on race and found your experiment. How long much longer will you be in Korea teaching English? I just moved to Denver and would love to chat with you about your experience!

Thanks! (Oh wow… that experiment was insane, haha.) I actually left Korea in 2010 and went to Taiwan after. I moved back to the US in 2011. Sounds good, I sent you an email.